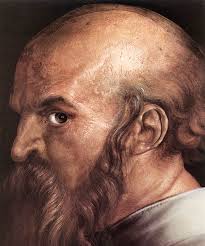

John Calvin on Free Will and Predestination

from Institutes of the Christian Religion (1537)

John Calvin, the French reformer, established a theocratic state in

Geneva, Switzerland, and his teachings eventually became the foundations for

Presbyterianism. In the first passage here from his Institutes he is explaining

how it can be that we humans can have free will yet can at the same time

inevitably sin. God is necessarily good, i.e., it is of his very nature to be

good; yet the fact that He cannot do anything evil is not a limitation on him,

i.e., does not show that he is lacking in some liberty.

Similarly, humans, even

though they necessarily fall into sinning, are still responsible for their

deeds, since those deeds are still done voluntarily. In the second passage

Calvin states his doctrine of predestination: God has foreknowledge of all that

will happen; all humans sin and deserve only condemnation, but God has

pre-ordained, at the beginning of time, who it is that He will graciously

save--in Calvin's words, "favored with the government of His Spirit."

We, of

course, cannot understand why some are saved and others not. (This very

difficult doctrine can be traced way back to the thought of St. Augustine, but

it is not a central element of his theology or of most Christian theology as it

is for Calvin's.)

How, according to Calvin, does God know all things, past, present and future?

Is it the way we humans do, or is it different?

Since we have seen that the domination of sin, from the time of its subjugation

of the first man, not only extends over the whole race, but also exclusively

possesses every soul; it now remains to be more closely investigated, whether we

are despoiled of all freedom, and, if any particle of it yet remain, how far its

power extends. . . .

Now when I assert that the will, being deprived of its liberty, is

necessarily drawn or led into evil, I should wonder if anyone considered it as a

harsh expression, since it has nothing in it absurd, nor is it unsanctioned by

the custom of good men. It offends those who know not how to distinguish between

necessity and compulsion.

But if anyone should ask them whether God is not

necessarily good, and whether the devil is not necessarily evil, what answer

will they make? For there is such a close connection between the goodness of God

and His divinity that His deity is not more necessary than His goodness. But the

devil is by his fall so alienated from communion with all that is good that he

can do nothing but what is evil.

But if anyone should sacrilegiously object that

little praise is due to God for His goodness, which He is constrained (1) to preserve, shall we not readily reply that His inability to do evil

arises from His infinite goodness and not from the impulse of violence?

Therefore if a necessity of doing well impairs not the liberty of the divine

will in doing well if the devil, who cannot but do evil, nevertheless sins

voluntarily; who then will assert that man sins less voluntarily, because he is

under a necessity of sinning?

This necessity Augustine everywhere maintains, and

even when he was pressed . . . he confidently expressed himself in these terms:

"By means of liberty it came to pass that man fell into sin; but now the penal

depravity consequent on it, instead of liberty, has introduced necessity." And

whenever the mention of this subject occurs, he hesitates not to speak in this

manner of the necessary servitude of sin.

We must therefore observe this grand

point of distinction, that man, having been corrupted by his fall, sins

voluntarily, not with reluctance or constraint; with the strongest propensity of

disposition, not with violent coercion; with the bias of his own passions, and

not with external compulsion: yet such is the pravity (2) of his nature that he cannot be excited and biased to anything but what

is evil. . . .

When the will of a natural man is said to be subject to the power of the devil, so as to be directed by it, the meaning is, not that it resists and is compelled to a reluctant submission, as masters compel slaves to an unwilling performance of their commands; but that, being fascinated by the fallacies of Satan, it necessarily submits itself to all his directions. For those whom the Lord does not favor with the government of His Spirit, He abandons in righteous judgment to the influence of Satan. . . .

When we attribute foreknowledge to God, we mean that all things have ever

been, and perpetually remain, before His eyes, so that to His knowledge nothing

is future or past, but all things are present: and present in such a manner that

He does not merely conceive of them from ideas formed in His mind, as things

remembered by us appear present to our minds, but really beholds and sees them

as if actually placed before Him.

And this foreknowledge extends to the whole

world and to all the creatures. Predestination we call the eternal decree of

God, by which He hath determined in Himself what He would have to become of

every individual of mankind. For they are not all created with a similar

destiny; but eternal life is foreordained for some, and eternal damnation for

others.

Translated by John Allen (1813)

(1) Forced.

(2) Depravity, corruption.

This is an excerpt from Reading About the World, Volume 2, edited by Paul Brians, Mary Gallwey, Douglas Hughes, Michael Myers, Michael Neville, Roger Schlesinger, Alice Spitzer, and Susan Swan and published by American Heritage Custom Books.

The reader was created for use in the World Civilization course at Washington State University.

Also see Pelagius Why was Right

- Pelagius was Right

- Original Sin an Overview

- Original Sin as seen from Judaism

- Dualism

- John Calvin: Free Will and Predestination

- Pelagius: To Demetrias, why he was cleared of heresy

- Pelagius: Chapters