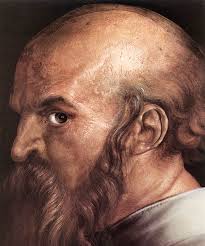

Reassessing an Apostle Yields Some Surprising New Theories

He never walked with Jesus of Nazareth, yet he traversed the Roman Empire proclaiming him the divine Christ. He never heard Jesus teach, yet he became Christianity's most influential expositor of doctrine.

He spoke little about Jesus's life, yet he attached cosmic significance to his death and Resurrection. The Apostle Paul, some scholars now believe, was more instrumental in the founding of Christianity than anyone else-even Jesus himself.

A tireless missionary and prolific theologian, Paul almost single-handedly transformed a fringe movement of messianic Jews into a vibrant new faith that, within a few generations, would sweep the Greco-Roman world and alter the course of Western

His preaching of salvation "by grace . . . through faith" in the Risen Lord has inspired spiritual seekers throughout the centuries.

Yet precisely because of his larger-than-life stature in the nascent Christian church, Paul always has been a figure surrounded by controversy.

In his own time, he was reviled by religious and political adversaries and arrested, beaten, exiled, and eventually executed for his zealous preaching in the Roman precincts of the Mediterranean rim. In more recent times, some have branded him a misogynist and a homophobe.

A scholarly quest. Today, in a batch of recent books and articles, critics and admirers alike have sought to penetrate what some contend are flawed interpretations and deliberate distortions of Paul's teachings.

Just as some have tried for centuries to uncover a "Jesus of history" unadorned by church tradition, many scholars now have taken up a Quest for the Historical Paul. Among the more provocative theories that have emerged from these studies:

- As a Christian missionary and theologian, Paul knew little and cared less about the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. More important in Paul's mind was the death and Resurrection of the exalted Christ who appeared to him in a mystical vision.

- Paul was intensely apocalyptic and believed that Christ's Second Coming was imminent. Consequently, he did not intend his sometimes stern judgments on doctrinal matters and on issues of gender and sexuality to become church dogma applied, as it has been, for nearly 2,000 years.

- Although an apostle to the gentiles, Paul remained thoroughly Jewish in his outlook and saw the Christian movement as a means of expanding and reforming traditional Judaism. He had no thought of starting a new religion.

- For all of his energy and influence, Paul wrote only a fraction of the New Testament letters that tradition ascribes to him, and even some of those were subsequently altered by others to reflect later developments in church theology.

As might be expected, these claims are passionately debated. In some quarters, the quest for a new and improved Paul is denounced as an ideological attack on the Bible and Christian tradition.

"Paul in the 20th century has been used and abused as much as in the first," says N. T. Wright, a New Testament scholar and dean of the Lichfield Cathedral in Staffordshire, England. Yet there is wide recognition among scholars of every stripe that to discover fresh insights into the life of the Apostle is to draw closer to the roots of Christianity.

Most of what is known of Paul comes from his own writings and from the Acts of the Apostles, a New Testament chronicle of the early church written decades after Paul's death. Though none of the writings are purely biographical, they provide revealing glimpses into his life and career. He was born Saul in the town of Tarsus in what is now southern Turkey, probably in about A.D. 10.

Educated in Jerusalem "at the feet of Gamaliel," grandson of the great Jewish sage Hillel, he joined the Pharisees, a party of strict constructionists of the Judaic laws.

Writing years later to Christians in Philippi, Paul proudly recounted his ethnic credentials: "Circumcised on the eighth day, a member of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew born of Hebrews; as to the law, a Pharisee; as to zeal, a persecutor of the church; as to righteousness under the law, blameless."

Little is known of his physical traits. In his second letter to the Corinthians, Paul spoke vaguely of a physical affliction-a "thorn in the flesh"-that he described as "a messenger of Satan to torment me, to keep me from being too elated."

Biblical scholars have speculated it could have been a physical malady such as epilepsy, malaria, or eye disease, while one commentator has suggested that Paul's torment may have been his own vexatious sexuality. In his 1991 book, Rescuing the Bible from Fundamentalism, Episcopal Bishop John Shelby Spong of Newark, N.J., depicted Paul as a repressed and self-loathing homosexual, a view that is not widely shared.

In his early career, according to both the Acts and his own letters, Paul was a zealous persecutor of Christians. Some scholars now believe he was part of a radical and sometimes violent faction of first-century Judaism known as the Shammaite Pharisees. The Shammaites, says Wright in What Saint Paul Really Said (1997), were followers of Shammai Ha-zaken, a Jerusalem sage who advocated a strict interpretation of Jewish law.

The meaning of zeal

While followers of his Pharisaic contemporary, Hillel, pursued a "live and let live" approach to political and religious adversaries, says Wright, the Shammaites believed the Torah "demanded that Israel be free from the Gentile yoke" even if by violent means. Thus, while for modern Christians, zeal is "something you do on your knees, or in evangelism, or in works of charity," says Wright, "for the first-century [Shammaites] 'zeal' was something you did with a knife." It was in that spirit of "holy war" that Saul of Tarsus pursued the Christian heretics-men, women, and children-who when caught were often beaten, imprisoned, and even executed.

But Paul's career as a persecutor of Christians came to a dramatic end on the road to Damascus. As the book of Acts tells it, Saul was on his way to arrest Christians in the Syrian city when: "a light from heaven flashed around him. He fell to the ground and heard a voice saying to him, 'Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?' He asked, 'Who are you, Lord?' The reply came, 'I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting. But get up and enter the city, and you will be told what you are to do.' "

Temporarily blinded, Saul was led away by his traveling companions. In Damascus, according to the text, he was "filled with the Holy Spirit" and regained his sight, was baptized, and immediately began proclaiming Jesus as "the Son of God."

He had received his call to be a "witness to all the world" and an apostle to the gentiles. Paul now believed that God had indeed begun to inaugurate a new age for Israel-just as the followers of Jesus whom he had persecuted had so passionately claimed.

Through his own direct encounter with the Risen Christ, say University of Massachusetts Prof. Richard Horsley and historian Neil Asher Silberman, Paul became convinced that Jesus's earlier incarnation as a poor Galilean peasant was "merely a prelude to his revelation as Israel's messianic redeemer," spoken of in the Hebrew scriptures.

Seeing God's plan. Yet as dramatic as it was, argue Horsley and Silberman in their 1997 book The Message and the Kingdom, Paul never considered his Damascus Road experience a "sudden [conversion] to a new religion." Instead, they argue, he found it a revelation of "previously unknown details of God's unfolding plan for Israel's salvation at the End of Days." What Paul then began to fervently preach was not a new faith but a refined and fulfilled version of the old.

Over the next two decades in three separate campaigns, Paul and his co-workers would travel the roads of the Roman Empire and the commercial sea lanes of the Aegean and Mediterranean, carrying the gospel to the cities of Asia Minor, Greece, and eventually to Rome. But the content of their message, some scholars argue, differed in important ways from the gospel others were preaching.

The mother church in Jerusalem, led by Jesus's brother James, had kept strong ties to traditional Judaism. Its members worshiped at the temple and carefully observed the Law of Moses.

As more and more gentiles joined the fellowship of believers, leaders of the Jerusalem church grew increasingly concerned that the laws of Judaism were being neglected, particularly the law requiring circumcision of male converts. The question threatening to fracture the young church was a crucial one: Did one need to become a Jew first to become a Christian?

Paul had not been among the original disciples of Jesus. Nor had he been converted by them. Consequently, he gave little deference to their views when they differed from what he believed Christ had revealed to him directly. He was summoned to Jerusalem to explain himself to the "pillars" of the Jerusalem church: the Apostles James, Peter, and John.

A compromise was reached that temporarily defused the issue: Circumcision would not be required of gentile converts, but following certain other Judaic rules would be expected.

Paul's mission to the gentiles would continue. But only with the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple by the Romans in A.D. 70 would the issue finally become moot. Christianity's Jewish wing disappeared in the aftermath, and the thriving gentile church continued to spread throughout the Roman Empire.

The split from Judaism was now assured. Christianity would become a separate faith shaped by Paul's vision of salvation through the Risen Savior, not by works under the old Mosaic Law.

British biographer A. N. Wilson, in his 1997 book Paul: The Mind of the Apostle, argues that Paul's Risen Christ had little to do with the historical Jesus. Christ was for Paul "not so much the man [the disciples] remembered (though of course he was that) but a presence of divine love in the hearts of believers."

There was no quoting of Jesus's parables or aphorisms in Paul's writings, adds Gregory C. Jenks, rector at St. Matthew's Anglican Church in Drayton, Australia. "The good news," for Paul, says Jenks, "focused on what God did in Jesus on the cross, and on his imminent appearance as Christ, the exalted one."

Some scholars argue that Paul simply may not have known of Jesus's teachings. J. Leslie Houlden, professor emeritus of theology at King's College in London, notes that Paul tells no stories of Jesus other than that of the Last Supper. While there are allusions in Paul's writings to some of Jesus's teachings, he notes, Paul "does not ascribe this to Jesus and, consequently, misses golden opportunities to say, 'As Jesus taught...'"

Building on Jesus

Other scholars argue that Paul's letters should not be considered in total isolation, as if they contain all that Paul knew, believed, and preached. Paul no doubt knew more about Jesus, they argue, and he knew his audience knew more as well. Paul, says Wright, was "building on the foundation" Jesus laid. He was "not building another one."

Of all of Paul's teachings, those that stir the most controversy today relate to homosexuality and the role of women in the church. Writing to his co-worker Timothy, Paul declares that a woman may not "teach or have authority over a man; she is to keep silent" in the church. And in a notorious passage in the letter to the Ephesians, he exhorts women to "submit yourselves unto your own husbands."

His views on homosexuality are equally provocative. Writing to Christians in Rome, he denounced those who he said had forsaken God's ways. Because of their wickedness, Paul wrote: "God gave them up to degrading passions. Their women exchanged natural intercourse for unnatural... Men committed shameless acts with men and received in their own persons the due penalty for their error."

But some scholars argue that Paul's views on those matters have been given much too wide a berth in Christian theology. Paul's high regard for women as coworkers is amply demonstrated in other letters. Scholars theorize that Paul's stern remarks were aimed at preserving order in worship rather than delineating the "place" of women in the natural order. Some even suggest that the most flagrant "anti-women" statements may have been added to the texts by later church scribes.

Paul's views on homosexuality also may have been misconstrued. Daryl D. Schmidt, professor of religion at Texas Christian University, contends that Paul was repulsed by what he saw as "unbridled passion" and "sexual addiction" that often took the form of same-sex contact in the bathhouses of the Greco-Roman world between men who would otherwise be considered straight. "It was not homosexuality as we understand it today as an orientation toward people of the same sex," says Schmidt.

Moreover, Paul believed that Christ's return was imminent-as did many Christians of that first generation. In his writings to the churches, argues Wilson, Paul was "not laying the ground rules for the Christian centuries, but getting ready for an imminent End." Although the consequences of his stringent condemnation might have been widespread, "they were not consequences which he could have foreseen himself."

The debate over the life and works of Paul is certain to continue, not least because it goes to the very character of Christianity itself-whether, as Houlden says, it is "a religion devoted to the perpetual imitation of Jesus and the following of his teachings" or a faith "centering on elicited response" to the exalted figure of Christ.

Whether or not Paul qualifies as Christianity's true founder, his impact on the shaping of that post-Easter faith makes the search for ever clearer portraits of the man a worthy endeavor.

- Jesus the Man

- Paul the Apostle and Salvation Thru Faith

- James, Paul, Dead Sea Scrolls by John Oller

- Theology of Paul

- Review of Hyam Maccoby's Paul and Hellenism by John Mann

- Paul's Bungling Attempt At Sounding Pharisaic by Hyam Maccoby

- Hyam Maccoby was Mostly Right

- Jesus Acted as a Pharisee

- Jesus, Jewish Resistance, Day of the Lord

- Paul's Companion St. Luke

- Maccoby's Theories Historical Jesus

- Problem of Paul Introduction

- Problem of Paul Part 1

- Problem of Paul Part 2

- Monotheism and the Messiah

- Jesus, Jewish Resistance, Pharisees

- Jesus, Jewish Resistance, King of the Jews