Elizabeth and the Puritans

by Will Durant

Against an apparently weaker enemy, a handful of Puritans, she did not prevail. They were men who had felt the influence of Calvin; some of them had visited Calvin's Geneva as Marian refugees; many of them had read the Bible in a translation made and annotated by Geneva Calvinists; some had heard or read the blasts of John Knox's trumpet; some may have heard echoes of Wyclif's Lollard "poor priests."

Taking the Bible as their infallible guide, they found nothing in it about the episcopal powers and sacerdotal vestments that Elizabeth had transferred from the Roman to the Anglican Church; on the contrary, they found much about presbyters' having no sovereign but Christ.

They acknowledged Elizabeth as head of the Church in England, but only to bar the pope; in their hearts they rejected any control of religion by the state, and aspired to control of the state by their religion. Toward 1564 they began to be called Puritans, a term of abuse because they demanded the purification of English Protestantism from all forms of faith and worship not found in the New Testament.

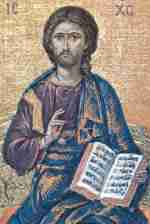

They took the doctrines of predestination, election, and damnation deeply to heart, and felt that hell could be escaped only by subordinating every aspect of life to religion and morality. As they read the Bible in the solemn Sundays of their homes, the figure of Christ almost disappeared against the background of the Old Testament's jealous and vengeful Jehovah.

The Puritan attack on Elizabeth took form (1569) when the lectures of Thomas Cartwright, professor of theology at Cambridge, stressed the contrast between the Presbyterian organization of the early Christian Church and the episcopalian structure of the Anglican Establishment.

Many of the faculty supported Cartwright, but John Whirgift, headmaster of Trinity College, denounced him to the Queen and secured his dismissal from the teaching staff (1570). Cartwright immigrated to Geneva, where, under Theodore de Beze, he imbibed the full ardor of Calvinist theocracy.

Returning to England, he shared with Walter Travers and others in formulating the Puritan conception of the Church. Christ, in their view, had arranged that all ecclesiastical authority should be vested in ministers and lay elders elected by each parish, province, and state. The consistories so formed should determine creed, ritual, and moral code in conformity with Scripture. They should have access to every home, power to enforce at least outward observance of "godly living," and the right to excommunicate recalcitrant and condemn heretics to death. The civil magistrates were to carry out these disciplinary decrees, but the state was to have no spiritual jurisdiction whatever.

The first English parish organized on these principles was set up at Wandsworth in 1572, and similar "presbyteries" sprang up in the eastern and middle counties. By this time the majority of the London Protestants, and of the House of Commons, were Puritans. The artisans of London, powerfully infiltrated by Calvinist refugees from France and the Netherlands, applauded the Puritan attack on episcopacy and ritual. The businessmen of the capital looked upon Puritanism as the bulwark of Protestantism 'against a Catholicism traditionally unsympathetic to "usury" and the middle classes.

Calvin was a bit too strict for them, but he had sanctioned interest and had recognized the virtues of industry and thrift. Even men close to the Queen had found some good in Puritanism; Cecil, Leicester, Valsingham, and Knollys hoped to use it as a foil to Catholicism if Mary Stuart reached the English throne.

But Elizabeth felt that the Puritan movement threatened the whole settlement by which she had planned to ease the religious strife. She thought of Calvinism as the doctrine of John Knox, whom she had never forgiven for his scorn of women rulers. She despised the Puritan dogmatism even more heartily than the Catholic.

She had a lingering fondness for the crucifix and other religious images, and when an iconoclastic fury destroyed paintings, statuary, and stained glass early in her reign, she awarded damages to the victims and forbade such actions in the future.

She was not finicky in her own language, but she resented the description which some Puritan had given of the Prayer Book as "culled and picked out of that popish dunghill, the Mass Book," and of the Court of High Commission as a "little stinking ditch." She saw in the popular election of ministers, and in the government of the Church by presbyteries and synods in dependent of the state, a republican threat to monarchy. Only her monarchical power, she thought, could keep England Protestant; popular suffrage would restore Catholicism.

She encouraged bishops to trouble the troublemakers. Archbishop Parker suppressed their publications, silenced them in the churches, and obstructed their assemblies. Puritan clergymen had organized groups for the public discussion of Scriptural passages; Elizabeth bade Parker put an end to these "prophesying"; he did. His successor, Edmund Grindal, tried to protect the Puritans; Elizabeth suspended him; and when he died (1583) she advanced to the Canterbury see her new chaplain, John Whitgift, who dedicated himself to the silencing of the Puritans.

He demanded of all English clergymen an oath accepting the Thirty-nine Articles, the Prayer Book, and the Queen's religious supremacy; he subpoenaed all objectors before the High Commission Court; and there they were subjected to such detailed and insistent inquiry into their conduct and belief that Cecil compared the procedure to the Spanish Inquisition.

The Puritan rebellion was intensified. A determined minority openly seceded from the Anglican Communion, and set up independent congregations that elected their own ministers and acknowledged no Episcopal control. In Robert Browne, a pupil (later an enemy) of Cartwright, and chief voice of these "Independents," "Separatists," or "Congregationalists," crossed over to Holland, and he published two tracts outlining a democratic constitution for Christianity.

Any group of Christians should have the right to organize itself for worship, formulate its own creed on the basis of Scripture, choose its own leaders, and live its religious life free from outside interference, acknowledging no rule but the Bible, no authority but Christ. Two of Browne's followers were arrested in England, were judged in contempt of the Queen's religious sovereignty, and were hanged (1583).

In the campaign for election to the Parliament of 1586 the Puritans waged oratorical war upon any candidate unsympathetic to their cause. One such was branded as a "common gamester and pot companion"; another was "much suspect of popery, cometh very seldom to his church, and is a whoremaster": those were days of virile speech. When Parliament convened, John Penry presented a petition for reform of the Church, and charged the bishops with responsibility for clerical abuses and popular paganism.

Whitgift ordered his arrest, but he was soon released. Antony Cope introduced a bill to abolish the entire episcopal establishment and reorganize English Christianity on the Presbyterian plan. Elizabeth ordered Parliament to remove the bill from discussion. Peter Wentworth rose to a question of parliamentary freedom, and four members supported him; Elizabeth had all five lodged in the Tower.

Frustrated in Parliament, Penry and other Puritans took to the press. Eluding Whitgift's severe censorship of publications, they deluged England (1588-89) with a succession of privately printed pamphlets, all signed "Martin Marprelate, Gentleman," and attacking the authority and personal character of the bishops in terms of satirical abuse. WJhitgift and the High Commission deployed all the machinery of espionage to find the authors and printers; but the printers moved from town to town, and public sympathy helped them to escape detection until April 1589.

Stung by these pamphlets, Elizabeth gave Whitgift a free hand to check the Puritans. The Marprelate printers were found, arrests multiplied, and executions followed. Cartwright was sentenced to death, but was pardoned by the Queen. Two leaders of the "Brownian Movement," John Greenwood and Henry Barrow, were hanged in 1593, and soon thereafter John Penry. Parliament decreed (1593) that anyone who questioned the Queen's religious supremacy, or persistently absented himself from Anglican services, or attended "any assemblies, conventiclers, or meetings under cover or pretense of any exercise of religion" should be imprisoned and unless he gave a pledge of future conformity, should leave England and never return, on pain of death.

At this juncture, and amid the turmoil and fury, a modest parson raised the controversy to the level of philosophy, piety, and stately prose. Richard Hooker was one of two clergymen assigned to conduct services in the London Temple; the other was Walter Travers, Cartwright's friend. In the morning sermon Hooker expounded the ecclesiastical polity of Elizabeth; in the afternoon Travers criticized that church government from the Puritan view. Each developed his sermons into a book.

As Hooker was writing literature as well as theology, he begged his bishop to transfer him to a quiet rural parsonage. So at Buncombe in Wiltshire he completed the first four books of his great work Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity. Three years later, at Bishopsbourne, he sent Book V to the press; and there, in 16oo, age forty-seven, he died.

His Laws astonished England by the calm and even-tempered dignity of its argument and the sonorous majesty of its almost Latin style. Cardinal Allen praised it as the best book that had yet come out of England; Pope Clement VIII lauded its eloquence and learning; Queen Elizabeth read it gratefully as a splendid apology for her religious government; the Puritans were mollified by the gentle clarity of its tone; and posterity received it as a noble attempt to harmonize religion and reason.

Hooker astonished his contemporaries by admitting that even a pope could be saved; he shocked the theologians by declaring that "the assurance of what we believe by the Word of God is to us not so certain as that which we perceive by sense"; man's reasoning faculty is also a divine gift and revelation.

Hooker based his theory of law on medieval philosophy as formulated by St. Thomas Aquinas, and he anticipated the "social contract" of Hobbes and Locke. After showing the need and boon of social organization, he argued that voluntary participation in a society implies consent to be governed by its laws. But the ultimate source of the laws is the community itself: a king or a parliament may issue laws only as the delegate or representatives of the community. "Law makes the king; the king's grant of any favor contrary to the law is void...For peaceable contentment on both sides, the assent of those who are governed seemed necessary Laws are not which public approbation has not made." And Hooker added a passage that might have warned Charles I:

The Parliament of England, together with the [ecclesiastical] Convocation annexed thereunto, is that whereupon the very essence of all government within this kingdom doth depend; it is even the body of the whole realm; it consisted of the king and of all that within the land are subject to him, for they are all there present, either in person, or by such as they voluntarily have derived [delegated] their power unto.

To Hooker religion seemed an integral part of the state, for social order and therefore even material prosperity depend on moral discipline, which collapses without religious inculcation and support. Consequently every state should provide religious training for its people. The Anglican Church might be imperfect, but so would be all institutions made and manned by the children of Adam. "He that goes about to persuade a multitude that they are not so well off as they ought to be, shall never want attentive and favorable hearers; because they know the manifold defects whereunto every kind of regiment [government I is subject, but the secret lets and difficulties, which in public proceedings are innumerable and inevitable, they have not ordinarily the judgment to consider."

Hooker's logic was too circular to be convincing, his learning too scholastic to meet the issues of his time, his shy spirit too thankful for order to understand the longing for liberty. The Puritans acknowledged his eloquence, but went on their way. Compelled to choose between their country and their faith, many of them emigrated, reversing the movement of Continental Protestants into England. Holland welcomed them, and English congregations rose at Middelburg, Leiden, and Amsterdam. They're the exiles and their offspring labored, taught, preached, and wrote, preparing with quiet passion for their triumphs in England and their fulfillment in America.

From Age of Reason Begins by Will Durant P. 24-28

- Scientific Case for a Transcendent God

- In Defense of Classical Deism

- Environmentalism is Still a Religion

- Europeans as Victims of (Muslim) Colonialism

- Fear and Loathing of Islam is not Islamophobia

- Exposing 'Non-Jewish Jews'

- An Overview Gnosticism

- Apostle Paul Founder of Christianity

- Apostle Paul versus Pelagius

- The Holocaust by Rabbi Meir Kahane

- Why Kahane was Right by Lewis Loflin

[ Challenge to Atheists 3 ] [ Challenge to Atheists 4 ]

[ Challenge to Atheists 5 ]

- Topics on Religion and Environmentalism

- Modern Deist Manifesto Based on Classical Deism

- Gnosticism as Explained by Bishop N. T. Wright

- Deist Critique of the Gospel of Mark

- Religious Syncretism and Christianity

- Classical Deist' View of Religion and Its Application Today

- Taking a Closer Look at Gnosticism and Christianity

- Thoughts on Theistic Evolution and Deism by Lewis Loflin

- My Answer to a Secular Fundamentalist by Lewis Loflin

- Separation of Pseudo-Religion and State

- Environmentalism Religion or Political Philosophy?

- Why Christian Morals Need to be Rejected

- Myth of Early Islam

- Sickness of Afghan-Muslim Culture

- Failure in Seattle Schools

- Saint Augustine and the Western Christian World-View

- St. Augustine and Original Sin in the West

- St. Augustine and Evolution

- Early Years of St Augustine

- St Augustine: Development of His Views

- St Augustine: Conversion and Ordination

- St. Augustine: Anti-Manicheanism and Pelagian Writings

- St Augustine: Manichean and Neoplatonist Period

- St. Augustine: Activity Against Donatism

- Additional Material on St. Augustine

- Notes on Neoplatonism

- Early Christian and Medieval Neoplatonism

- Pelagius and why he was right.

- How Christianity drew on Philo's synthesis of Judaism and Hellenism